The Big Deception

Maybe the most important form of copaganda

I write today about The Big Deception. That’s my cute term for how the news misleads people about the processes by which public safety policies come to be. I’ve gestured at the concept in some of my writing, but I haven’t yet been explicit about it because I’ve been struggling to figure out how to write about it.

But recently, I had an interaction with the New York Times in which the paper agreed with my criticism and corrected an article after I pointed out on Twitter that the article’s description of the motivations of the NYC Mayor and NY Governor was deceptive (more on this incident later). This interaction made me think it was time to try to write more fully about how news reporting about why politicians do things contributes to mass delusion.

When I say “mass delusion,” I do not mean anything necessarily nefarious or conspiratorial. I’m not complaining about the use of bad crime statistics or quoting biased sources. Instead, I’m making the following observation: the level at which the news typically discusses the reasons that important public safety policies exist is superficial, simplistic, and wrong in ways that have discernible patterns and observable consequences in how well-meaning people approach trying to improve our society. If our theory about why things are happening is silly, then we won’t be able to do much about the things we don’t like.

This series will have three parts. In Part 1 this week, I’ll describe the basic concept, explain why it matters for how we think and what we do, and give an example about how the news can make us ignorant about why powerful institutions do the things that they do in the name of public safety. In Part 2 next week, I’ll describe the most obvious level at which The Big Deception operates: reporting on why politicians say they do things versus why they actually do things. I’ll give some revealing examples from news stories and probably say mean things about Eric Adams. In Part 3 the following week, I’ll explain a deeper level of deception always below the surface in public safety reporting: a focus on individual decisions of powerful people and not on the structures that determine the conditions in which those decisions are made. I’ll conclude with some advice to journalists and news consumers about how to mitigate The Big Deception.

Part I: Understanding The Big Deception

1) Introduction: What is “The Big Deception”?

The crux of the Big Deception is this: the collective effect of a variety of news media practices is to give people the wrong impressions about why consequential things happen in our society. Most people—including and especially progressive people who think of themselves as well-informed news consumers—are made ignorant about the real forces determining things that matter to their lives. As a result, many smart people who care about making our world better have a poor understanding of the kinds of things they should get involved in or support because their theory of political change is naïve and premised on misinformation. To put it crudely, the news media misleads people about how politics and power work.

One illustration of The Big Deception is that reporting on the punishment bureaucracy makes people think that “law enforcement” and punishment policies are the result of some reasonable weighing of good policy arguments as opposed to the product of organized interests asserting their power. On this view, further investments in police, prosecutors, and prisons are the natural, good faith response to “crime” (or to short term fluctuations in crime) and not, say, pursued because such investments produce profit, provide the ruling class with tools of surveillance and control, and further racial and economic objectives, etc.

We see this assumption that punishment policies are pursued for good faith safety reasons in virtually every aspect of contemporary crime reporting: from the phrases used within news stories to suggest that officials are pursuing such policies out of genuine concern for addressing safety, to when officials are quoted about their “public safety” motivations without skepticism or fact-checking, to the focus on the intentions of individual officials in the first place, to the absence in most articles of critical perspectives that posit different reasons for the growth of the punishment bureaucracy other than a genuine pursuit of safety for all, to the daily editorial decisions that juxtapose things like drug use, homicide, youth violence, or homelessness with police/prosecutor/prison policies and not, say, reporting on housing, public health infrastructure, early childhood education, toxic masculinity, or the isolation/alienation inherent in contemporary monopoly capitalism. The very choice to center police, prosecutors, and prisons in many discussions about various policy responses to social harms is a subtle but powerful form of deception.1

2) Why Does The Big Deception Matter?

In terms of public safety discourse, a lack of understanding about why things happen and, thus, how to change them, leads to all kinds of specific consequences in the behavior of the news media, ordinary people, and even people in power themselves:

Focusing on relatively inconsequential issues or political squabbles while ignoring issues of greater significance in determining outcomes for the things they care about;

Blaming the wrong people and institutions for things they don’t like;

Spending time working on social change strategies that won’t work (much of the non-profit world’s approach to reforming the criminal punishment bureaucracy is the equivalent of trying to stop oil drilling by presenting Exxon executives and Saudi government officials with a report by scientists linking fossil fuels with global warming and then inviting them to a panel discussion about it);

Donating money to others who are spending time on strategies that won’t work;

Designing rules, policies, or laws that misunderstand how to solve a problem or that pay insufficient attention to how existing systems might not be able to implement them despite their intentions;

Promoting reforms that lead to the same problems recurring because the underlying causes were not addressed;

Choosing careers and jobs that don’t satisfy them or ultimately advance the things they care about;

Arguing about the motivations and character of particular politicians, bureaucrats, or pundits instead of always focusing on structural northstars like reducing inequality, limiting the concentration of wealth, and ensuring meaningful transparency and accountability;

Focusing disproportionately on individual political candidates and politicians instead of building effective and long-lasting institutions, relationships, political formations, technologies, and interventions.

Before discussing the media, let me give you two examples from my own life about why this matters. I have spent almost a decade filing lawsuits and otherwise advocating against the cash bail system in the U.S., which jails millions of people every year solely because their families cannot access enough cash to buy their freedom through a private insurance company. If my theory for why that system exists is that people in power are genuinely trying to pursue overall public safety, equality, and justice, I might adopt particular strategies. And in that world, things might actually appear pretty easy. I might, for example, simply try to sit down and explain to legislators and to the multi-billion dollar for-profit bail industry the overwhelming social scientific evidence about how cash bail not only does not promote safety or court appearance, but leads to more crime in the future, lower rates of court appearances, and enormous economic and public health costs because of the lives destroyed by its discriminatory detention. Hopefully they would agree, and the bail system as we know it would go away. Yay.

However, if my theory for why the bail system looks like it does emphasizes that it is profitable for several multi-billion dollar industries that benefit from expanding the jail and pretrial supervision bureaucracies and that police, prosecutors, and judges rely on mass pretrial detention as a critical way to produce enough quick guilty pleas in low-level cases to keep the system from collapsing, I might adopt different strategies. Things might be much more complicated than just making the most persuasive arguments, however, because we would be fighting against multiple organized interests who have come to rely on the cash bail system to function bureaucratically in the society with the highest levels of arrest and prosecution in world history.

Similarly, the theory of what interests created something we hope to challenge helps us prepare for the predictable responses that opposing forces will make to being challenged. For example, financial interests underlying the bail industry and jail telecommunications industries might morph from selling bail bonds or jail phone calls into selling electronic monitoring and drug tests to people released without bail bonds. To do this, they may push for the creation of an entirely new pretrial supervision industry if they see the bail industry under threat. Or police, prosecutors, and judges might attempt to shift from wealth-based detention of our clients to detaining our clients in even larger numbers on other grounds. For example, after a well-meaning campaign by prominent lawyers eliminated wealth-based detention in federal court on the basis of the supposed unfairness to the poor in 1984, actual pretrial detention in federal courts tripled in the following decades from 24% to 72% of all arrested individuals, and the people detained were more disproportionately poor, Black, and immigrant than they were before the well-meaning “reform.”

Similarly, I recently completed a detailed investigation into the history of body cameras. One theory about why body camera sales exploded after Michael Brown’s killing in 2014 was that police and other people in power suddenly became interested in “accountability” and “transparency.” As I will show when that work is published soon, this is the theory almost exclusively represented in hundreds of news media stories discussing body cameras. However, another theory would be that multi-billion dollar companies and police across the U.S. had been trying to expand police surveillance technology for years, and their dream was every cop in the U.S. having a mobile surveillance camera that the cop controlled. The police, an army of police consultants, and several powerful companies wanted desperately to secure jointly beneficial, lucrative cloud computing contracts, facial and voice recognition database infrastructure, predictive policing surveillance algorithms, and ongoing cash for software training, maintenance, updates, and storage. Prosecutors wanted body cameras also, because they understood the value of video evidence curated by cops in securing quick convictions and in getting people to plead guilty and to give up their trial rights, which would enable more arrests, more prosecutions, and more leverage for increased fines, fees, and other punishment. But these corporate and government actors were unable to convince most cities to give them the billions of dollars it would take, until they came up with the idea to use their own violence in order to portray the greatest expansion of police surveillance systems in modern history as an initiative to hold police “accountable.” Seen this way, the explosion of body cameras was actually the result of a careful corporate plan embraced by punishment bureaucrats for reasons almost entirely the opposite of “accountability” and “transparency.”

Here is me illustrating this point:2

This is simplified to make a point: developing an accurate understanding of why things happen and what forces are pushing for them to happen along a longer causal chain is essential to predicting what will happen and to building any meaningful theory of how to change things.

I want to make three overall observations about this as you read my examples of media coverage in this series. First, you’ll notice that, in Worldview 1, the strategy is much simpler because once people in power are informed of the best arguments, they voluntarily improve things. This approach emphasizes rational good-faith thinking as the foundation of public safety policy and de-emphasizes the role of mapping and contesting power in social change. The media overwhelmingly presents something like Worldview 1, and this leads to brainworms in the minds of news consumers concerning how to achieve social change.

Second, what is the skill-set that advocates and well-meaning people need for Worldview 1? Largely it relies on a certain kind of analysis and rational argument—something lawyers and highly educated researchers, for example, are very good at. Now, I’m all for making the best arguments and using evidence and rational thinking—and that must be a part of any meaningful social change effort, but is it the only set of skills necessary, or even the most important? So, what about Worldview 2? This is much more complex. You need organizers—people who understand how to build relationships and power. You need courage. You need critical analysis. You need specialists in narrative. You need experts in systems and implementation because you know that you cannot trust government bureaucracy to implement something even once a policymaker is convinced it is a good idea in theory. And so on.3

Third, and probably most important, when you start to develop a more complex perspective on the causal chain for why policies come to be, you understand that the modern non-profit world’s push toward specialization and working in silos is ineffective. What you recognize right away is that the amount of change that comes from working only on bail reform or only on sentencing reform or only on body cameras or, even, only on “criminal justice reform” in its own silo is extremely limited. The interests promoting the cash bail system are essentially the same as the interests promoting police surveillance technology, constructing prisons, more fines/fees, and longer sentences. It’s largely the same set of interests who benefit from all bureaucracies of repression and control, which are largely owned by and operated for the benefit of interests representing the same social classes. And they are extracting this wealth from and controlling other classes of people, who are themselves the same in each example. This also means that it is impossible to pursue “criminal justice reform” without talking about bigger issues like health care, housing, inequality, education, racism, migration, etc. In order to fight against either the bail system or police surveillance, one needs to build broader power that can contest the deeper reasons those systems exist, and this requires not just making good arguments in one particular area, but a much broader political coalition with a much broader social base with much broader narrative explanations that are targeting bigger picture features of our society that simply cannot be fixed by the hyper-specialization pushed by the political and philanthropic classes.

My thesis in this series is that daily news media overwhelmingly confines itself to Worldview 1, and as a result, a lot of well-meaning people spend a lot of time making arguments as if we are in Worldview 1.

3) An Example of the Big Deception: The War on Drugs

a. How the reasons for the drug war were portrayed

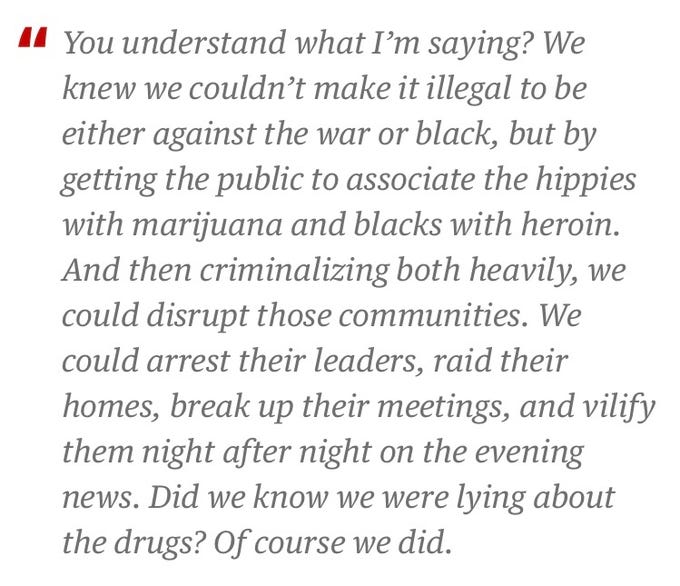

Let’s take the War on Drugs. The public statements by politicians in the news media about their asserted reasons for the War on Drugs bear no semblance to the actual reasons that ruling class elites embarked on the drug war. We now know this because of bombshell admissions from Nixon officials after the fact:

But we also know this because drug policy is an area in which we have overwhelming evidence: more police, prosecutors, and prisons don’t reduce drug use, addiction, overdose deaths, or improve public health. Instead, they make them worse and lead to other catastrophic harms. Despite the stated reasons for the drug war being contrary to available evidence, the news media has largely reinforced the stated reasons of politicians for several decades in daily news stories without providing the evidence that people could use to develop skepticism about those stated reasons.

Over forty years into the War on Drugs, the following are true:

The U.S. has spent trillions of dollars; detained tens of millions of people for hundreds of millions of years; separated tens of millions of children from parents; chemically destroyed millions of acres of rainforest and pristine ecosystems in Latin America; killed hundreds of thousands of people; stopped, searched, sexually violated, and arrested hundreds of millions of people; surveilled the communications of billions of people globally; stolen billions of dollars in property from poor people through civil forfeiture; deported hundreds of thousands of people; deprived tens of millions of people of highly effective therapeutic treatments for cancer, mental illness, PTSD, chronic pain, etc.; caused millions of people to become infected with infectious diseases; kicked millions of families out of public housing and public benefits; put tens of millions of poor people into an endless cycle of debt; and cost tens of millions of people their jobs at the cost of hundreds of billions of dollars to the economy.

The use of prohibited drugs has increased, prohibited drugs are more potent than ever, and overdose deaths have skyrocketed to their highest levels in U.S. history.

People in power making drug policy are not universally incompetent. Most of the people crafting U.S. drug policy know the above facts.

Every federal, state, and local official I’ve ever spoken with has known what I just wrote. Perhaps such fools exist, but I’ve never met a public official who believes that prosecution, punishment, and prisons are an effective way to reduce drug use, even assuming that is a genuine goal. Throughout the entirety of my time working on crack cocaine cases, every major government and academic body had repeatedly concluded there was no policy or scientific basis for the 100:1 disparity between punishment of crack cocaine and powder cocaine. The DOJ and then Congress nonetheless enforced and reaffirmed the disparity even after Congress reduced it to 18:1 (a random number it chose for no publicly articulated reasons).

They will admit this in private, just as Nixon officials did. A U.S. attorney prosecuting my client for a non-violent drug offense (and seeking 10 years to life in prison) once confided to me in the parking lot outside the federal courthouse that he and his colleagues knew that sending my client to prison and potentially sending their newborn child to foster care would not do anyone any good. The Big Deception keeps the public from understanding all of the reasons that the U.S. government was doing it anyway.

In spite of this reality-based consensus, time and again for decades, in news stories in every city throughout the U.S., the drug war was frequently portrayed as a good faith effort to reduce drug use. Here is how the New York Times, in 1971, casually described Nixon’s good faith efforts when he “tried to get at the problem”:

Here is how the New York Times described the motivations of Nelson Rockefeller in passing some of the most repressive drug laws in U.S. history:

Here is how the New York Times, uncritically and with no contrary context (and certainly no explanation of the U.S. government’s role in creating and controlling the international drug trade), allowed Ronald Reagan to describe the reasons for new federal legislation increasing imprisonment for drugs in 1986, including “the Government’s desire”:

Partly because of how the news media uncritically reported on the “law enforcement” approach to drugs, a lot of well-meaning people never appreciated for decades how much of a failure the drug war was, at least if failure was measured by the asserted public health goals of reducing the supposed harms of drug use. Many people assumed, based on media coverage of drug busts and penalties, that more enforcement and punishment was a natural response being pursued in good faith by people and institutions whose primary goal is reducing the supposed harms of drug use.

b. How the drug war is covered today

The news media, to this day, continues to report on empirically baseless authoritarian interventions as good faith attempts to reduce drug use. Just take a look at this San Francisco Chronicle article! Yikes. And that is how daily news media is largely reporting on the latest surge in targeting and punishing fentanyl cases.4 The unmistakable assumption underlying the aggregate of news media reporting on drugs is that people in power continue to wage the drug war because they believe that the costs are worth the benefits of their policies and because they do not have readily available alternatives. Take a look at how the Associated Press recently reported on increased prison sentences for fentanyl crimes—including sentencing people to die in prison—in Alabama in April 2023:

Although these policies are like climate science denial based on all available evidence, the Associated Press, which is not an outlier, portrays the proposals as good faith attempts by political leaders to “try to respond to the deadly overdose crisis” and “an effort to combat what has been called the deadliest overdose crisis in U.S. history.” This is amazing. Not only does the article tell readers nothing about any of the contrary scientific evidence, but officials pursuing policies that we know make the problem worse are treated as genuinely trying to help. This is important propaganda because it contributes to 1) mythologies about the good intentions of the ruling class despite the wealth of scholarly evidence on more likely reasons behind the drug war; and 2) mythologies about how policies are driven by the intentions of discrete groups of political leaders and not deeper structural conditions.

And this is how the Big Deception goes beyond perpetuating ignorance about the full scope of the drug war’s failure. For years since I first started defending people against drug prosecutions, I have talked to a lot of liberals, progressives, and moderates who describe themselves as generally against the War on Drugs. Even among well-meaning people who vaguely understand the broad failure of the drug war, many think that ineffective and harmful drug policies are the result of punishment bureaucrats (1) pursuing the limited strategies available to them the best they can; and (2) merely lacking sufficient information about the costs and benefits. Many of these people still view the War on Drugs as a natural effort to reduce the perceived harms associated with drug use. Even after forty years of failure, they continue to sympathize with the good intentions of officials who are trying to lock up fentanyl dealers. This assumption about good intentions is the only way that officials in every U.S. city are not met with open ridicule at pursuing such ineffective and harmful policies. And a focus on their intentions distracts from why absurd policies persist despite their abject failure.

Many of these well-meaning people I’ve spoken to had never thought that providing housing, free medical care, or universal basic income was the natural response to concerns about public drug use—none of those structural solutions were offered by the ruling class as the natural response to drug use. I believe that is at least partially because punishment was presented as an unquestioned solution to the problem in the news when reality was quite different: drug use was not a problem that the ruling class cared about urgently because they cared about the health and well-being of all people. It was not a problem that they actively viewed as so threatening to human existence that they carefully calculated all of the extraordinary human and financial costs and found them worth it. Instead, the expansion of the machinery of state power and profit was, in many overlapping ways, the impetus to search for policies like what became the war on drugs. The war on drugs itself was a solution in search of a problem.

Notice a couple consequences of this media deception. First, because the reporting on drugs typically omits the evidence about costs and benefits of drug prohibition and enforcement from each individual news story like the Associated Press article above, people in power are able to avoid urgent confrontation about why their assertions about their own motivations are so different from the evidence.

Second, because people are not being informed about the institutional benefits of the drug war to particular political, racial, bureaucratic, and financial interests in our society, they are largely unable to develop an accurate theory of why the drug war is still happening. For example, almost no daily news article on drug arrests or prosecutions discusses the benefits of current drug policies to private prisons, pharmaceutical companies, police unions, the bail bond industry, the multi-billion dollar jail telecommunications industry, probation officers, prosecutors, real estate developers, police surveillance companies, and business and property owners who benefit from giving government bureaucrats the justification, tools, and technology to have the discretion to police and control the poor, racial minorities, and immigrants near their properties.

If one believes the news media narrative of good faith pursuit of public well-being, then one would simply need to present evidence of its catastrophic failures and people in power in Alabama or Eric Adams would say “Oh my goodness, we didn’t realize there was a social science consensus about this for decades. We’ll stop immediately.” Given the good faith news framing, many well-meaning progressives therefore become convinced either that the policies are the best we have been able to come up with in a difficult situation or that we are just a few more studies, a few more panels at conferences, and a few more expert commissions away from convincing our enlightened leaders that they can achieve a better world!5

To the contrary, if all of the above interests were identified by news media in daily stories about drugs and punishment, as well as the amount of money and political influence they devote to preserving drug enforcement as it exists, people might develop a different view of why those policies persist and a different sense of the strategies that might be useful for someone who wanted to put an end to those policies to pursue.

Although the connection between this Big Deception and our views about how to create social change is sometimes hard for people to notice in the crime reporting context, because of a shift in mainstream media coverage in recent years, many progressive people are able readily to understand the same point in other contexts, such as global warming. Most progressives no longer believe that the problem with tackling global warming is that powerful institutions are not aware of it and don’t have alternatives available. But, for example, if the news subtly suggested every day for years that Exxon is pursuing more drilling because it cares deeply about global ecological sustainability but does not yet appreciate the impact of drilling on climate change or the harms of climate change, the news-reading public might develop a different strategy for stopping that drilling than if the news reporting suggested that Exxon is pursuing more drilling because it is pursuing profit. Understanding why institutions with power do things matters for how we should try to change things.

In Part 2, I’ll dig into the media coverage of the motivations of powerful people and walk through a hypothetical example of a local politician proposing to bring back an undercover police unit.

If I published thousands of stories of the course of a decade and hundreds of thousands of stories nationwide just mentioning two concepts together—such as policing and sentencing polices and crime—people would necessarily start to develop a view that they might be causally connected. Similarly, if the news media hardly ever juxtaposes two things—say, early childhood education or free medical care or wealth inequality and crime—the public may fail to draw any connection between them. In either case, the public’s understanding of the significant causes of crime may be distorted.

Chart courtesy of the amazing Nika Soon-Shiong.

You may need methods of conflict resolution, mutual aid, care, and protection from corporate and police adversaries.

There are some exceptions to this deceptive reporting, and those exceptions prove how easily drugs could be covered differently as a public health issue.

Ironically, the federal government rejected the recommendation in the 1970s by a heavily stacked “law enforcement” commission to not criminalize marijuana.

Alec, I have to say your analysis strikes me as having exactly the same issues in immigration policy. That is, there are the same forces at work leveraging their deception in the punishment bureaucracy to jail and deport immigrants and have politicians making anti-immigration policies to support their money stream. Good work.

This is such great analysis. The Big Deception that you describe is so universal and so ingrained that it creates cognitive dissonance, denial, and even anger in people when one tries to do what you are doing here, which is to explain (and illustrate extremely well!) the inherent exploitative incentives and mechanisms that underly so much of what we think of as the best and most “natural” ways in which to conduct ourselves and to organize our institutions and laws for the greater good, including our nation’s founding goals of Liberty, Equality, and Justice for all.

Our Fourth Estate (the press), in particular, has completely failed in the charge that it was given by our Constitution, of being “We, The People’s” guardians in relentlessly investigating and exposing governmental and institutional corruption, overreach, incompetence, and misadventure of just the sort you describe.

Addressing all of this in ways that are accessible and compelling to the sort of broad coalition that could make a difference in all of this is a daunting, but absolutely essential, lift. Thanks for putting your strong backbone into it!