The News and Public Opinion About Police

LA Times readers become less informed after they read the news.

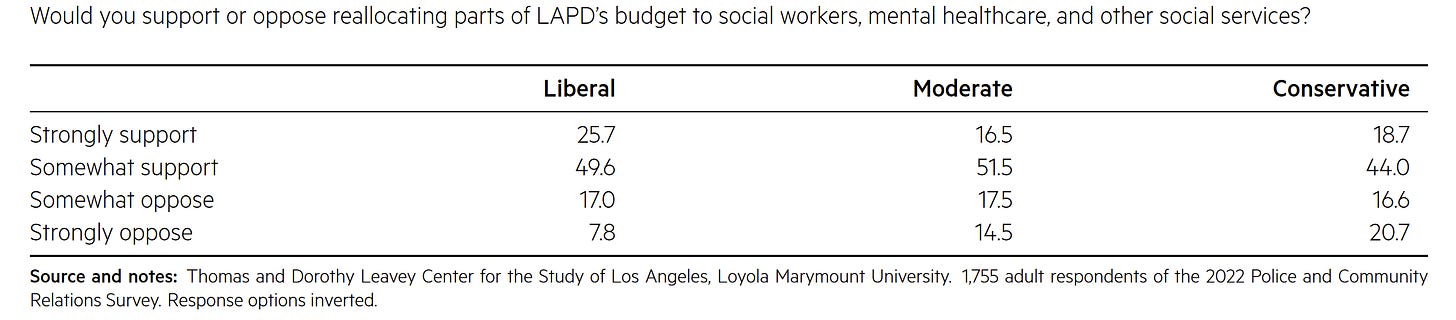

The results of a recent Loyola Marymount University poll are stunning. They should shake public discourse. 63% of conservatives, 68% of moderates, and 76% of liberals support "reallocating parts of LAPD’s budget to social workers, mental healthcare, and other social services.”

Overall, support for reallocating parts of LAPD budget to social services was almost 70%. But wait, haven’t we been told by pundit after pundit and article after article that it is conventional wisdom that the public wants higher police budgets? It is difficult to find anything that 70% of people in the U.S. support, let alone significant majorities across all demographic groups and political identities.

In some respects, another of the poll’s findings is even more revealing. Support for reallocating the police budget to social services is higher among people who live with a cop than people who don’t:

There is so much to say about this, but this post is going to be about how the media covered this poll. If you’re getting this newsletter, it probably won’t surprise you that the above findings were ignored and omitted by the news media.

Enter The Los Angeles Times

The Los Angeles Times published an article about this poll and didn’t report the findings I just mentioned. Here was the headline:

And here are a few key passages:

The article focused on how most people in Los Angeles had a favorable view of the police generally but that, despite these favorable views, people believe the police are racially biased. But take a look at how the LA Times covered the issue of defunding the police:

It’s worth examining how misleading and lacking in seriousness this is. What did the survey mean by “defund the police”? How does the LA Times want readers to understand that term? What does it mean that, when asked about the vague, much-maligned term “defund” people didn’t support it, but when asked specifically if they wanted to reallocate money from police to social services people overwhelmingly want to do that? These are important questions, and our news media is not helping our society discuss them in a thoughtful, complete, evidence-based way.

The effect of the LA Times reporting anti-”defund” sentiments, but omitting for readers that when asked the more detailed question of whether people support reallocating portions of LAPD budget to other social services, is that the LA Times did something very political.

The crux of virtually every “defund” campaign I’ve heard of in every city is taking some money from police budgets and using that money for mental health, emergency non-police response units, permanent supportive housing, education, nd other social services. That is literally what the fights are about in local government all over the country. But LA Times not only ignores this part of the survey most relevant to active political debates in Los Angeles, but it misleads readers that residents of Los Angeles don’t support those current proposals when *they do actually support them* in overwhelming numbers. (Especially those residents who live with police officers and who know best what they do and what they are capable of.)

It is hard to overstate the importance of this kind of media manipulation. Journalists and politicians have ridiculed the term “defund the police,” ironically critiquing it as vague. But they rarely discuss what it might actually mean to various segments of the public and even more rarely discuss what it means to the people actually using that term to build social movements and local political campaigns with specific budget priorities. Politicians, police unions, and journalists are thus often able to hide from the public the extraordinary support among wide swaths of the population to reduce some of the spending of the bloated police bureaucracy in favor of things that overwhelming evidence shows are actually more connected to safety.

The upshot: by keeping everything confusing and vague and never actually talking about the details of police budgets and what alternatives might look like, elite news outlets help powerful people concoct a “conventional wisdom” that is far different from the details about what people actually think.1

The Broader Lack of Rigor

Last year, I was invited to give a guest lecture at one of the top political science departments in the U.S. A group of professors took me out to dinner, and we started to discuss “defunding the police.” It was amazing how unserious the discussion was in many respects. For starters, different professors had different definitions of the concept and talked past each other, no one had an actual understanding of how the police bureaucracy works, where most of the budgets go, the level of spending on police public relations and surveillance technology, or the history of U.S. policing. Almost everyone kept pointing out that it was a foolish idea to discuss the topic because “the public doesn’t support defund” and so it would never happen. (I promised to keep identities secret.)

The conversation mirrored a conversation I’ve had with dozens of journalists at leading outlets. Many of these reporters will casually tell me that “people don’t support defund” and that “progressives will get killed because of defund.” But when I ask them what defund the police means, I get a wide range of mutually exclusive answers.2 Most strikingly, when I probe what this confident view is based on, it is almost always based on a general sense reporters get from hearing about public opinion in other news stories.

This is a huge topic and there is a lot more to say about it. But I want to end with a few basic points: our perception of the popularity of certain ideas depends a great deal on 1) how polls ask the question, 2) what background facts people are given before they answer, and 3) which aspects of a poll the media chooses to report. Each of these vectors takes place in the context of a public discussion pervaded by misinformation about police and in a society that devotes more resources to its profitable punishment bureaucracies than any society in recorded history. The issue of police budgets is thus a great example of how unserious a discussion can become in this perfect storm of incompetence and incentive to distort. We need a serious news media that views its role as explaining, clarifying, and probing complex issue with helpful insight, examples, evidence, and context. Instead we have a news media that simplifies, omits, and distorts in service of power.

* * *

Let me finally acknowledge my bias. I have spent 17 years working in and studying the criminal punishment bureaucracy in some fashion and have come firmly to the belief that U.S. society’s massive expenditures on the punishment bureaucracy do not make us safer, and that instead police, prosecutors, probation, parole, private profiteers, and prisons serve to control and surveil marginalized populations and to crush progressive social movements. Based on my conversations with thousands of people in communities across the country, I also believe that this view is commonly held and would be even more commonly held if people were getting more complete and factual information about how government punishment bureaucracies are (mal)functioning. I write about this in my book Usual Cruelty and here and here. I believe that one of the major reasons copaganda is so prevalent is that it is widely understood among punishment bureaucrats that they could not justify virtually any aspect of the current U.S. punishment bureaucracy if ordinary people had full information about it.

A deeper problem beyond the scope of this post is how widespread propaganda and misinformation distort what people report as their opinion. In my own experience talking to people about this issue across the country, self-reported opinions vary widely depending on how the question is asked and on what baseline factual information is conveyed prior to asking the question.

When I ask them if racial desegregation or MLK Jr. himself were treated as popular by the contemporaneous mainstream press, or theft of land from indigenous people or women voting, etc. I get blank stares. But the lack of understanding among many reporters of how social movements function and how power is built is a topic for another post.

What you write about and what you have to say about it are among my very favorite things I read! Thank you. I so look forward to your email.