A few years ago, when I was first investigating the rise of modern debtors’ prisons across the U.S., I had a conversation with a news editor that I’ll never forget.

As I did to anyone who was unlucky enough to speak with me during that period of my life, I explained that 100,000s of human beings were being jailed each year across the U.S. solely because they owed debts. This was a huge story for many reasons, I said, including because it was illegal, because it was separating families and killing people, and because it revealed widespread racist and predatory behavior by local police, prosecutors, judges, and private debt-collection and probation companies in several thousand cities. I asked the editor to do a story on it. The editor declined. Why? According to the news outlet, another reporter who I had worked with had “already covered the debtors’ prison story a few months ago.”

I have had many dozens of conversations like this since then, but that was the first time in my career I had been forced viscerally to confront questions about what is considered “newsworthy” and what isn’t.

The editor’s explanation also raised for me several important questions about the nature of news. What does it mean to have “already covered” a massive social problem that continues happening unabated to new people each day? Whenever there is a plane crash, news editors do not decline to cover it on account of having covered a previous crash. Why are some issues easily conceptualized as a single news story—“the debtors’ prison story”—while other stories are seen as continuously plentiful sources of daily news to be covered from the same and different angles each night, such as the “surge in shoplifting”? One might just as easily think that there are thousands of great, urgent stories (and many different angles to each) when so many families are being illegally separated because of their poverty in the wealthiest country in the world. What does the editor’s use of the phrase “a few months ago” suggest about how reporters and editors are making difficult subjective evaluations about the urgency and importance of each of the many millions of things they could choose to tell us about or that they could choose to ignore?1

Just recently, I got a similar response from a different editor when I asked a major news outlet outlet to do a story on the more than 400,000 human beings jailed across the U.S. for the holidays because their families cannot pay cash bail—rampant constitutional violations that empircally make everyone in our society less safe, cost tens of billions of dollars, spread infectious disease, and devastate families for generations. The editor told me: “There have been other good stories on the bail system this year.”

And so, I followed with great interest the last few weeks when, in a two-week period in December 2022, the New York Times published three long articles about a supposed “shortage” of police officers in the United States. One was a lengthy elaboration on police union talking points, including that we need more police, that police need more money, and that this “shortage” is a crisis. Another was a separate NYT story that was actually just an interview with the first reporter elaborating on the police union talking points from the first story. And the third was essentially a carbon copy of the same talking points a couple weeks later with many of the same sources, this time including some skeptical civil rights advocates for some “both sides” context.

You can tell which stories elites care about by their volume

One of the most overlooked aspects of contemporary news analysis is an examination of how the sheer volume of certain news stories distorts our understanding of what is important. I’m working on a larger research project about this with some colleagues, but I want to sketch out a few initial thoughts here.

Some examples:

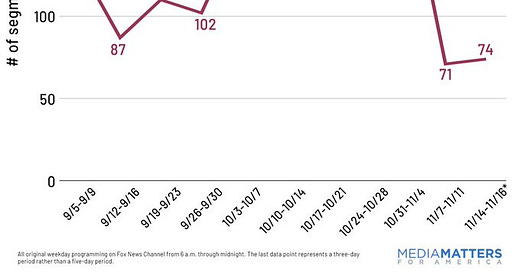

To illustrate the point in a general way, I picked a few examples that I think are revealing. Let’s start with the low-hanging fruit. Courtesy of Washington Post journalist Philip Bump, take a look at how the volume of crime segments on Fox News, CNN, and MSNBC ballooned as the U.S. neared election season:

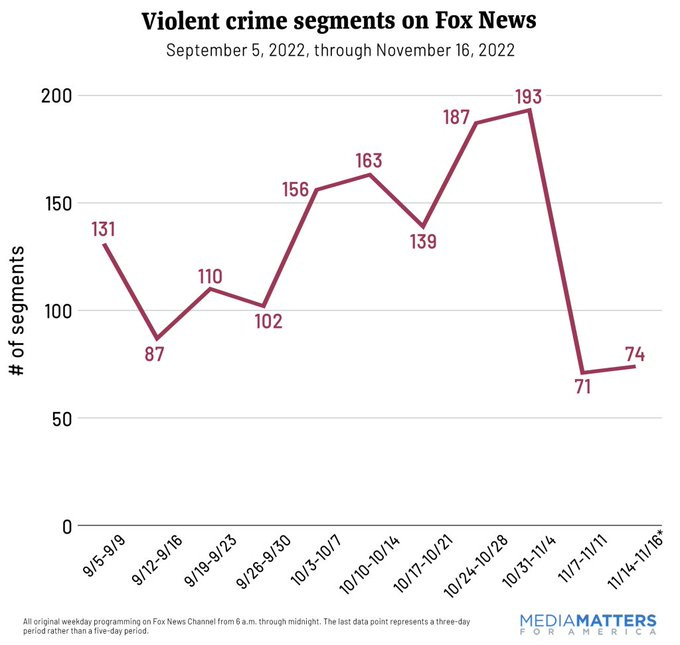

Take a look at what happened on Fox News as soon as the midterm election was over:

What you are seeing is that Fox News is a sophisticated political propaganda operation that understands the importance of news volume. As many others have pointed out, the volume of this coverage is not linked to factual reality in terms of police-reported crime rates. But it is linked to a political agenda, and Fox News understands very well that the number of times a story is told dramatically affects how many people hear about it and how urgent people think it is.

To take another example, below you’ll find a chart from a fantastic Bloomberg data investigation by two reporters who looked at the volume of “violent crime” coverage. Take a look at what happens to local news stories in New York City when Eric Adams is elected Mayor:

Now take a look at this graph from the Bloomberg journalists. It shows that the volume of mentions of shootings in New York media was not connected to the number of shootings:

According to an analysis by fwd.us, the news media did the same thing with bail reform and crime in New York—and the increases were linked to political developments like elections and delibarations over rolling back the bail reforms—even though all objective evidence showed that bail reform did not increase crime:

Finally, in the summer of 2021, a right-wing local journalist posted a 21-second video of an alleged shoplifting in San Francisco. If you recall, this was during a public relations push by Walgreens, police unions, far-right media, and billionaire-funded DA recall activists to drive fear around “retail theft” that mainstream media quickly and weirdly adopted. The fantastic journalists at Fairness & Accuracy In Reporting (FAIR) did an analysis and found that this single video spawned 309 separate articles about the Walgreens incident in the 28 days after it was posted. The researchers found that there was not a single article about a multi-million dollar wage theft settlement paid out by Walgreens to its California employees. (On January 5, 2023, after I wrote this essay, a Walgreens executive admitted publicly that the company had overblown their claims about retail theft.)

For some shoplifting perspective, think about how few articles are run in major corporate outlets on far larger property crimes that lead to enormous suffering and death: $50 billion in wage theft, $830 billion in corporate securities fraud, and $1 trillion in tax evasion each year to take just a few white collar crimes. For months though, rather than reporting on these larger problems with high volume news, there was a frenzy of article after article in news outlet after news outlet about a crisis of retail theft. Take a look at a screenshot from my phone of the homepage of the San Francisco Chronicle on November 22, 2021:

How can we think about all this?

First, I want to make an initial meta point: crime coverage broadly is in some respects a good illustration of this phenomenon. The volume of news stories every day on police reported crimes dwarfs their relative importance on any conceivable metric of objective global and domestic harm. Many people in the U.S. are woefully uninformed about matters of extreme importance, and yet daily news stories in major corporate media inundate them with stories about individual crimes. While there might be one story yearly on a local TV news station about air pollution deaths or unsafe drinking water in an area or global poverty or lack of access to preventative health care or price gauging of life-saving medicines, there are daily stories about crimes sourced to local and national police officials. This affects which harmful things we feel afraid of and which we never think about.

Second, news volume concerning public safety is not driven by transparent, accountable principles that are objective. News outlets make myriad subjective judgment calls pursuant to processes that are not made public to readers/viewers and that are often not written down or audited after the fact. According to editors I’ve spoken to, outlets do not even evaluate how many stories of certain kinds featuring certain sources get published in any given time period. It’s remarkable that a field that is so important to everything in our collective lives has not developed more rigorous practices for evaluating potential biases in how it is selecting which stories to emphasize.

Instead, the volume of fear-mongering crime news is often driven by factors that everyone would agree should not determine newsworthiness: local police PR spending, particular relationships between reporters and sources that are cultivated through for-profit consultants and elite social circles, timing of political events like budget season or legislative votes on policies like bail rules (bail supposedly became a scandal when police wanted it to for political reasons divorced from data about crimes committed on bail), police union negotiations, the cultural or political interests of journalists and their social groups, and by certain media events, like an election. More generally, the amount of coverage is driven by political agendas of prominent people who can use their platform to lead the media. Editors have, over the years in my conversations with them, justified covering objectively less important things by saying that they are simply covering what the elected politicians are talking about. But here’s the bottom line: in any of these cases, it’s not some objective analysis of total global human and environmental well-being, safety, and death. It’s subjective.

This subjectivity means lots of biases. For example, local news seems to think that a bad thing is worthy of high volume coverage if poor people are doing it—always, but especially if poor people are doing the bad thing to rich people. But when rich people are doing something bad to hundreds of thousands of poor people, it’s viewed as a niche story for a single investigative piece, not daily breaking news that the outlet must make sure everyone is aware of.

In my experience, reporters and editors use a lot of little tricks to tell themselves that these decisions are “objective.” There are so many ways to make a story seem fresh when ultimately it is the same story. Thus, reporters tend to use these tricks to explain why this shoplifting of a Rolex is different from last week’s shoplifting of a deodorant by a different person. But when writing about systemic constitutional violations in the money bail system, for example, reporters have often told me that it’s the “same story” when a judge violates the constitutional rights of the Rolex thief in the same way as a different judge violated the rights of the deodorant thief.

But what often seems to be determining these decisions is not that there is something objectively more newsworthy about a shoplifting crime than a crime committed by prosecutors and judges (intentionally violating constitutional rights is a federal felony crime, even though it is never prosecuted). Instead, it has to do with the underlying reason that powerful people and dominant media cultural norms want something to be news. When officials are trying to use the media to increase investments in police and prisons, there are many ways to make a low-level crime appear totally novel: each theft is a separate event. In this story it’s a theft from Macy’s, in that story it’s a theft from CVS. In this one a railroad theft!

It’s true that there often hasn’t yet been a story about any particular theft. But beyond those details, the actual story is the same, and it could be covered like the news media covers many social justice issues: with one in-depth story every few months about trends. But the individual stories of what is happening to the most vulnerable people in our society don’t matter as much unless it’s a story about a crime they committed.

When doing systemic justice work, those of us to who talk to the media a lot know that the onus is always on us to come up with a new angle to make the story seem different. This is really a bad situation if the story you really need to tell in high volume is that our society continues to do a lot of the same things every day that are really really bad and that harm the world’s vulnerable people, animals, and ecosystems in basically the same ways every day.

Method of news delivery

One final point. News volume isn’t just about how many articles media outlets decide to devote to particular subjects. It’s also about how they get those articles to us.2 For example, dedicated teams at most big media outlets now spend a lot of time and money deciding which of their stories to promote in various ways, including by putting them on social media and sending push notifications to our phones. They also make editorial decisions about which stories get daily follow up:

Which stories get sent to the news outlet’s other verticals: the daily podcast, the web tv show, the weekly roundup newsletter, etc…?

Which get the “live blog” treatment with multiple reporters assigned to it?

Which gets promoted on Twitter and Instagram, and which aspects of each story are pulled out for wide promotion?

Which gets selected for cross-over stories on the nightly TV news joint partnerships?

Which stories are so important that they get day after day of follow-up coverage, with new stories written not just about the story but about what people are saying and feeling about the first story?

Think about what a different cultural sense of urgency the U.S. would have if, for example, there was a push notification for every time a police officer illegally stopped, searched, and arrested someone. Or a push notification for every illegal eviction in our neighborhood. Or a push notification for every toxic spill that threatens our waterways, or for every time a local polluter exceeded emissions requirements for toxic gas? The urgent priorities of U.S. news consumers would look a lot different than they do:

The threat posed by information volume is by no means isolated to formal “news.” Neighborhood apps like NextDoor and the frightening new dystopian app Citizen have tens of millions of users receiving push notifications about police-reported crime around them all the time. It is into this culture of surveillance and fear (and huge profit) that news organizations are using push notifications about crime to compete for fear-based attention.

For at least the last 8 years, the New York Times has been putting enormous money and employee time with specialized teams into building a strategy for push notifications to mobile phones. A full analysis of this is beyond the scope of this post, but it’s important to note that these decisions are being made based on business directives and not on an objective editorial analysis of which stories are the most important for the well-being of our world.

I don’t purport to offer anything close to a full analysis of these important issues in this post. For a more full exploration of this concept in the context of crime coverage, I recommend Stuart Hall’s landmark book Policing the Crisis, published in 1978.

In the 1980s, the executive editor of the New York Times, A.M. Rosenthal, explained: “Every journalist knows that a story on the front pate or its television equivalent can interest the whole country, but that the same story, inside, often has no impact at all.” As discussed in this section, journalists understand that this principle extends well beyond the physical placement of an article in a hard copy of the paper (or the modern equivalent of its placement on a website).

We are so fucked. Every day brings new confirmation and this newsletter does an excellent job of explaining more reasons for why things are shit. Thank you. Sincerely.

I found this to be a very provocative read. Well done