Exciting News

My new project becomes public

Friends,

I want to share something very special to me. I have not posted here recently because I am converting these newsletters into a book, Copaganda, which will be published by the New Press.1 But, another reason for my silence is that I have been working on several exciting new projects at Civil Rights Corps. (Thanks to those of you who make optional donations to this otherwise free newsletter because every little bit helps us do our important civil rights cases!) Last week, we made public two landmark new cases that I hope will be among the most important things I ever work on. I want to tell you about them now briefly, both because of their connection to copaganda and because they represent something shocking, but also inspiring.

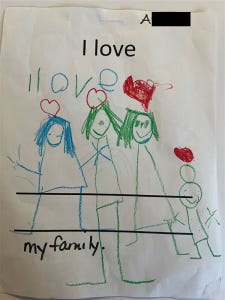

The image above comes from the sidewalk outside the jail in Flint, Michigan. The children of Flint go down to the jail and write messages to their moms and dads in chalk. Their parents can look down from their cages and see the messages, which help given them hope inside a jail with horrific conditions. But why must the children communicate like this? Because the jail in Flint, like hundreds of other jails across the U.S., has banned family visits. Every year, several million children are now banned from hugging their parent, looking into their eyes, or holding their hands.

The story of how this happened is the subject of two new lawsuits against two counties in Michigan. The cases allege that Sheriffs in Michigan and across the U.S. conspired with multi-billion dollar jail telecom monopolies to ban family visits. The theory? By banning families from visiting loved ones for free, many of these extremely poor families will be forced to pay exorbitent rates for phone and video calls. The telecom companies make hundreds of millions each year by contracting for local jail monopolies, and the suit alleges that they promised to kickback a percentage of the increased revenues from the banning of visits to Sheriffs. Many of the contracts also require the jail population to remain at certain capacities to ensure enough profit. I very much encourage you to read the legal complaints here. The children we are representing are absolutely incredible and so brave.

So, where does copaganda come in? Well, you might recall that, in 2020, the Sheriff in Flint gained national media attention by putting down his weapon, marching with protestors, and telling them that the police “loved” them. I wrote an op-ed about it at the time. He now has billboards up across the state touting his great values. As you’ll see from the complaints, we uncovered that this same Sheriff is the one who negotiated the telecom contract to profit from banning family visits, and the complaint details some egregious internal emails bragging about the financial windfall in both counties we sued. It’s such an amazing example of the gap that copaganda creates between the image and reality of who police are and what they do.

In a devastating coda, as I was standing outside photographing the messages of chalk love from kids, employees came out from the jail and washed them away. I guess they didn’t even want the parents confined in the jail—many of whom are only there for months or years because their families lack cash to pay money bail even though they are presumed innocent—to be able to see what their kids wrote to them.

This is the kind of work we have done for almost ten years, and the kind of work that we are going to continue to do as long as we can. Fighting authoritarianism and the way that our society has become desensitized to mass human caging—and identifying the ways that a small group of people profit from it—is difficult work but it’s very important in changing the conversations our society has about public safety. I hope you’ll help us with that work by sharing stories like this, which help show people that the decisions the punishment bureaucracy makes are often not about overall well-being, but are done to serve other interests. And keep an eye out this week for a long feature in the New Yorker magazine about it.

-alec

As with my last book, Usual Cruelty, the publisher and I again hope to have free copies available for all teachers, students, and people in jail or prison.

Thank you for all you do. You are one of my heroes.

I so appreciate your work, Alec. Family separation policies are so evil, in all their forms. Like all punitive measures, they just add trauma to trauma. Grateful that you see another possible world, and for your tireless efforts in working toward it.